It is a reality of financial markets that market declines are made worse by forced sellers.

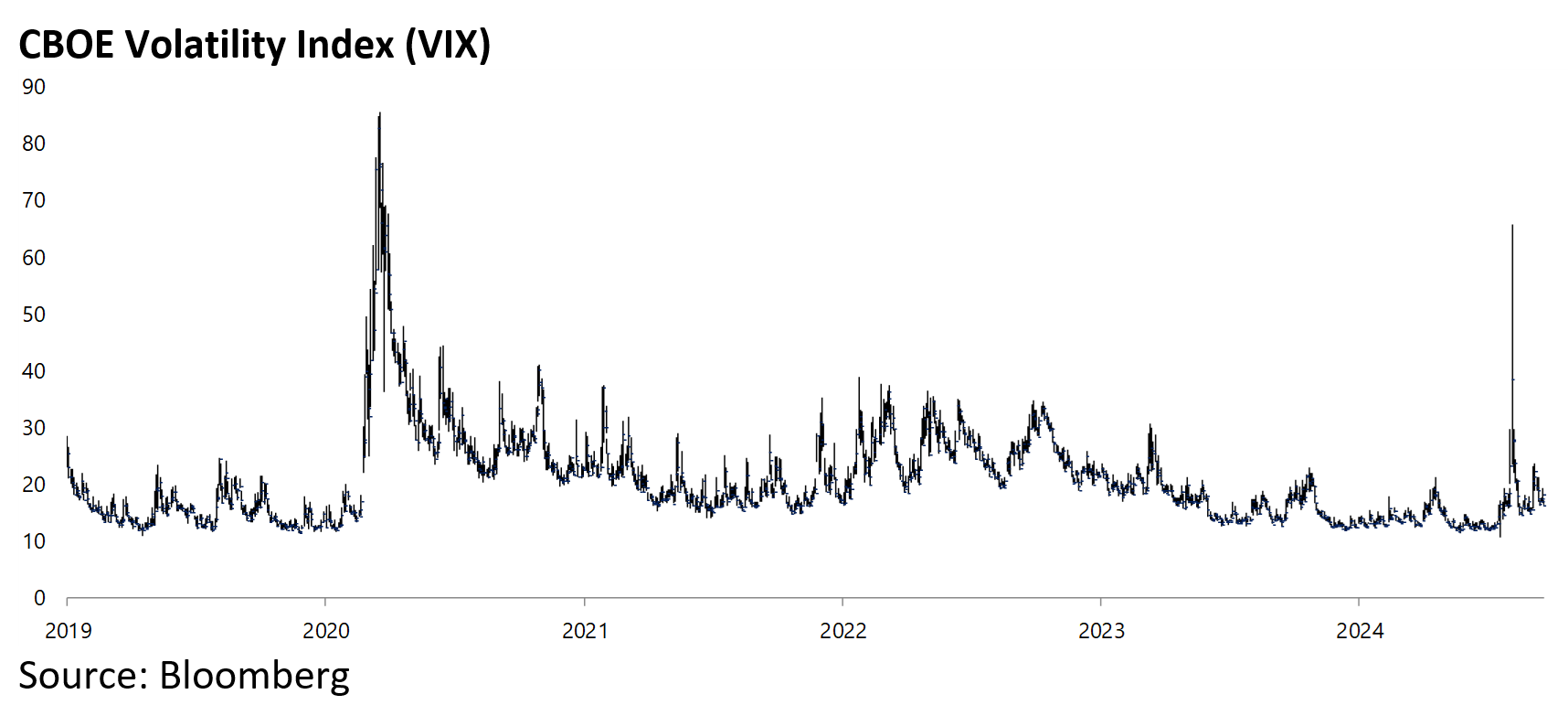

The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) surged from 16.4 at the end of July to an intraday high of 65.7 on 5 August, the highest level since March 2020, in the recent yen carry trade-triggered unwind, though it has since declined to 16.3.

The stocks were sold because they were listed and therefore, unfortunately, relatively easy to sell compared with the likes of CDOs and related securitised mortgage derivatives for which bids disappeared almost entirely.

Unfortunately, listed securities are now in danger of another wave of forced selling from investors over exposed to illiquid investments.

This writer was reminded of this risk reading an analysis published in July on the exposure of US endowments to private equity (see “A Private Equity Liquidity Squeeze By Any Other Name” by Markov Processes International, 15 July 2024).

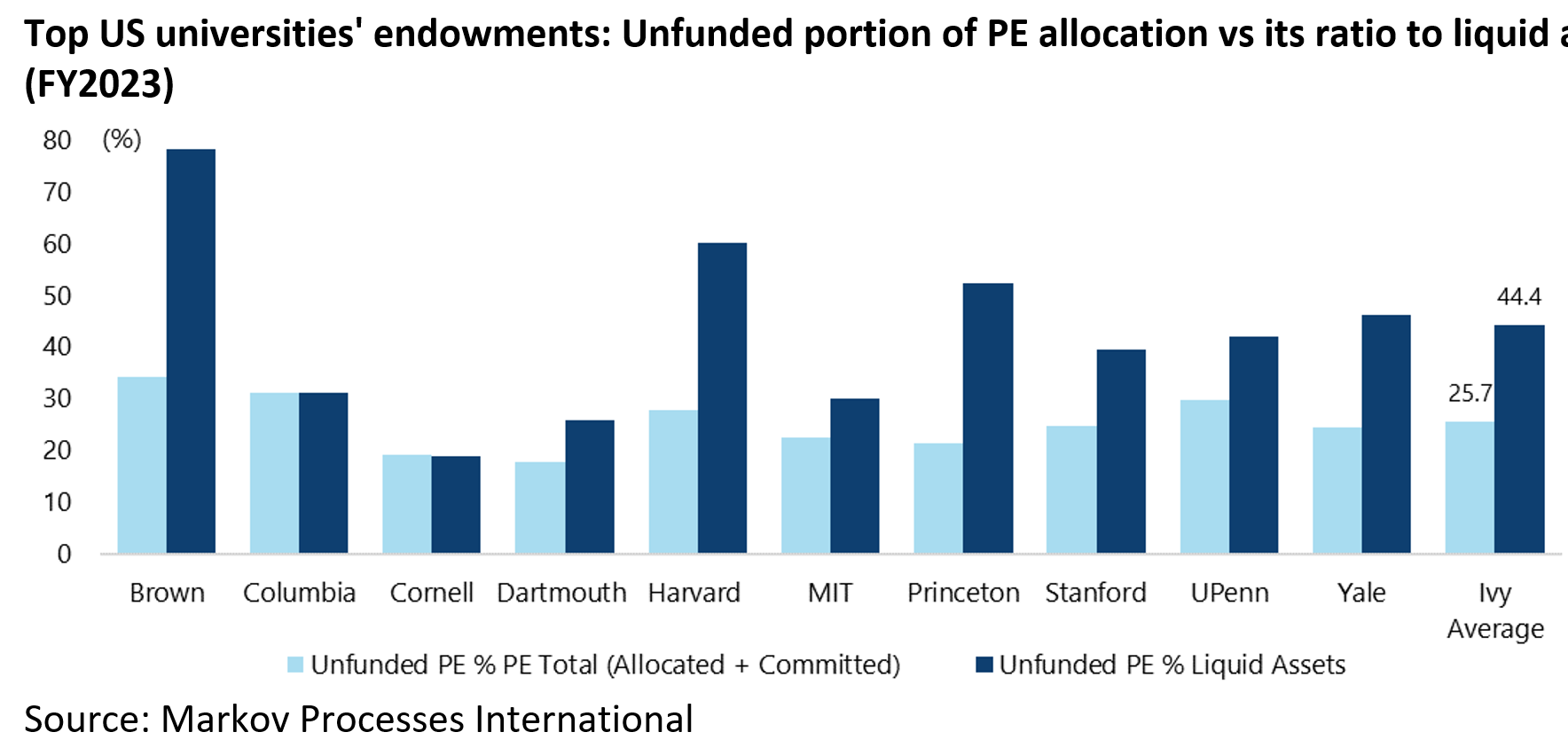

The report analyses the private equity portfolios and related liquidity positions of ten top US universities.

Markov estimates that at the end of fiscal year 2023, which is apparently 30 June for such institutions, the average Ivy League institution had 37% of its endowment in private equity (defined as PE and venture capital) based on an analysis of annual reports and financial statements.

This compares with about 30% allocated to more liquid asset classes of which stocks comprised about 20% and cash and bonds 10.5%.

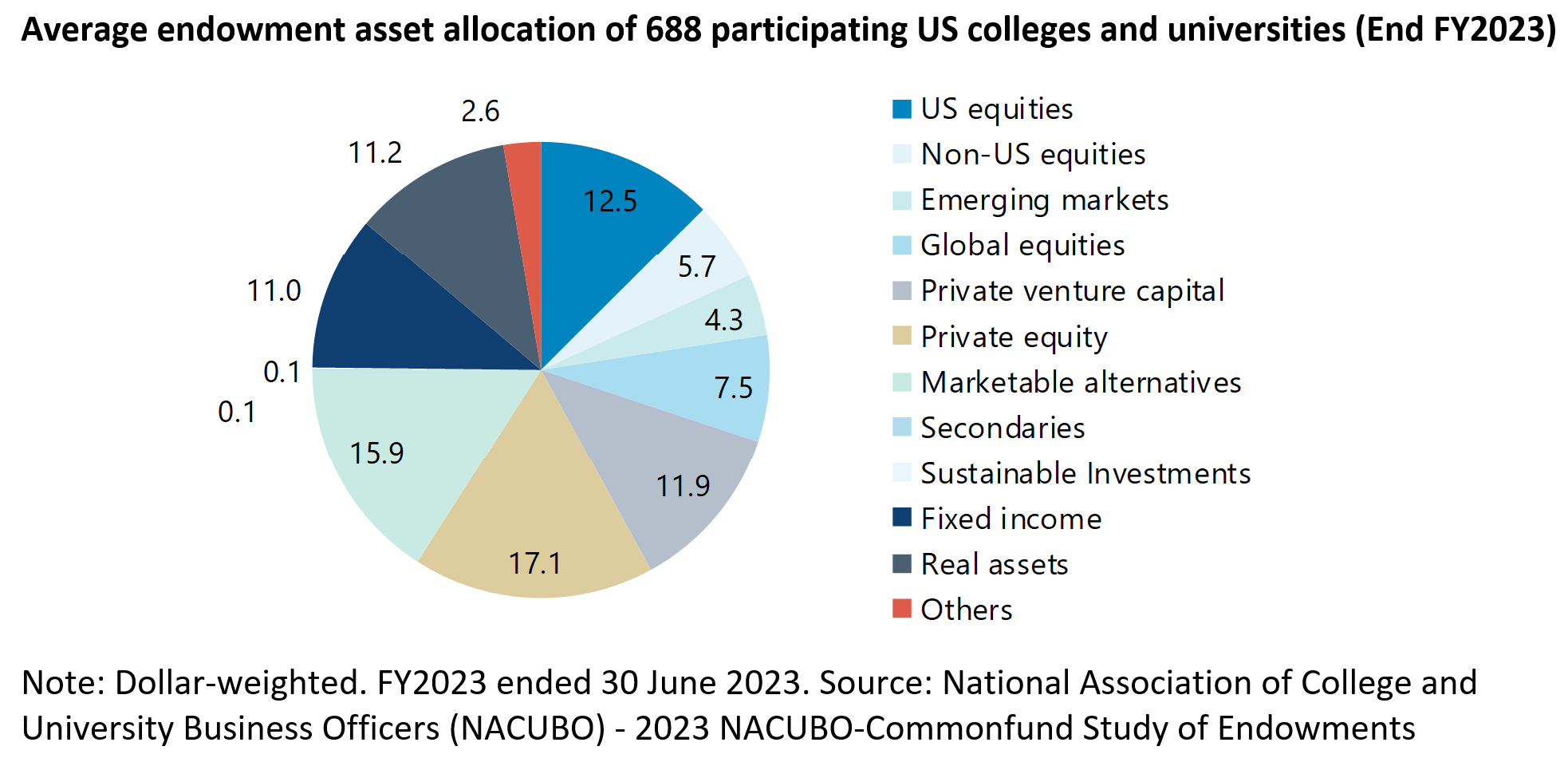

As for a broader universe of US endowments, the Markov report also noted that, based on a 2023 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments published by the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), 29% of the US$839bn in endowment assets of 688 surveyed colleges and universities were allocated to private equity (17% in PE and 12% in VC) at the end of FY23.

If the allocation of 16% to hedge funds and 11% to real assets such as property is added, then the asset allocation is over 50% to what the recommended Markov study describes as “alternatives of various illiquidity levels”.

Clearly “alternative” has become a buzzword in the post-2008 investment world where asset allocators have rushed to embrace all things “alternative”, just as they were equally committed until recently to proclaim their investments as “sustainable”, whatever that particular word means exactly.

Yet this writer can remember when “alternative” was once a word synonymous with the counter culture and proponents of psychedelics such as Timothy Leary.

Alternatives Won’t be the Winning Assets Going Forward

But back to the present the practical reality for now is that the higher the exposure to alternatives the more illiquid the portfolio.

Thus, the Markov report notes that distributions by some of the biggest private equity firms fell sharply last year, whereas in a normal year distributions would be enough to fund capital calls.

This relates to the issue of the 28,000 companies globally which Bain & Co. estimates that the PE industry wants to bring to market globally this year in a report published in March (see Bain & Co. report: “Global Private Equity Report 2024”, 11 March 2024).

That suggests a potentially huge pipeline for investment bankers globally, but will there be the demand for all that stock, and at what valuations?

True, the commencement of a renewed Federal Reserve easing cycle, with the 50bp cut last week, offers a relief to the PE industry which is by its very nature leveraged.

But that may come as cold comfort if lower interest rates coincide with an economic downturn.

Meanwhile, the Markov report poses a rhetorical question in terms of how institutions such as endowments will respond if there is an intensifying liquidity squeeze.

Will they sell more liquid stocks and bonds or will they unload “locked up” PE funds at a discount in the secondary market as such a secondary market does exist, as previously discussed here (see “Tracking three risks that could sink markets: Oil, geopolitics and private debt”, 13 May 2024).

The answer is probably a bit of both, though a key variable is how mature is the investment in PE.

In this respect, the older the investment the better since the exit is still likely to be at a profit even though the valuation will probably be lower than the previous funding round.

On this point, Markov notes that the higher the portion of an endowment’s PE allocation that is unfunded, the younger the average vintage of an endowment’s PE portfolio, which in turn means that the cash distributions from the existing PE portfolio will be lower to meet future capital calls.

Markov estimates that the Ivy League average unfunded PE allocation as a percentage of liquid assets is 44%, while its unfunded PE commitments are at 26% of the total allocated and committed capital.

Liquid assets are defined as the sum of cash, bonds and equity allocations.

Clearly, US Ivy League endowments are not the only institutions which have been investing in private equity.

But they seem to have led the charge to embrace “alternatives” based on the so-called “Yale Model” pioneered by David Swensen, the chief investment officer at Yale University from 1985 until his death in 2021, who was responsible for managing Yale University’s endowment assets.

The Yale Model allocates more to alternative investments such as private equity, venture capital, hedge funds and real estate.

To sum up, the alternative industry not only represents a competitive threat which has sucked assets out of the conventional asset management industry in recent years.

But the potential fallout from its current liquidity squeeze creates the risk of another wave of forced selling of listed securities.

The views expressed in Chris Wood’s column on Grizzle reflect Chris Wood’s personal opinion only, and they have not been reviewed or endorsed by Jefferies. The information in the column has not been reviewed or verified by Jefferies. None of Jefferies, its affiliates or employees, directors or officers shall have any liability whatsoever in connection with the content published on this website.

The opinions provided in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice. Readers should assume that the author and/or employees of Grizzle hold positions in the company or companies mentioned in the article. For more information, please see our Content Disclaimer.