There was an interesting study published recently that US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen felt obligated to respond to in public by rejecting the claim made that the Treasury has manipulated the issuance of Treasuries in a way that lowers real borrowing rates and, therefore, undermines the impact of Federal Reserve tightening.

This was a paper published by Hudson Bay Capital and written by economist Nouriel Roubini and former Treasury official Stephen Miran (see Hudson Bay Capital report: “ATI: Activist Treasury Issuance and the Tug-of-War Over Monetary Policy”, 22 July 2024).

The paper focused on one aspect of the growing blurring of monetary and fiscal policies which has been one consequence of the quanto easing era.

That is the growing resort of the Treasury in the recent past to short-term bill issuance, a point relating to the fast-deteriorating fiscal situation in the US.

The authors of the report call this growing resort to short-term funding “activist Treasury issuance” (ATI).

They argue that the Treasury’s decision last autumn to increase significantly short-term bill issuance lowered the 10-year Treasury bond yield by 25bp.

Whatever the accuracy of such an estimate, it is certainly the case that the quarterly refunding announcement on 1 November marked the catalyst for the rally with the 10-year Treasury bond yield peaking at 5.02% in late October.

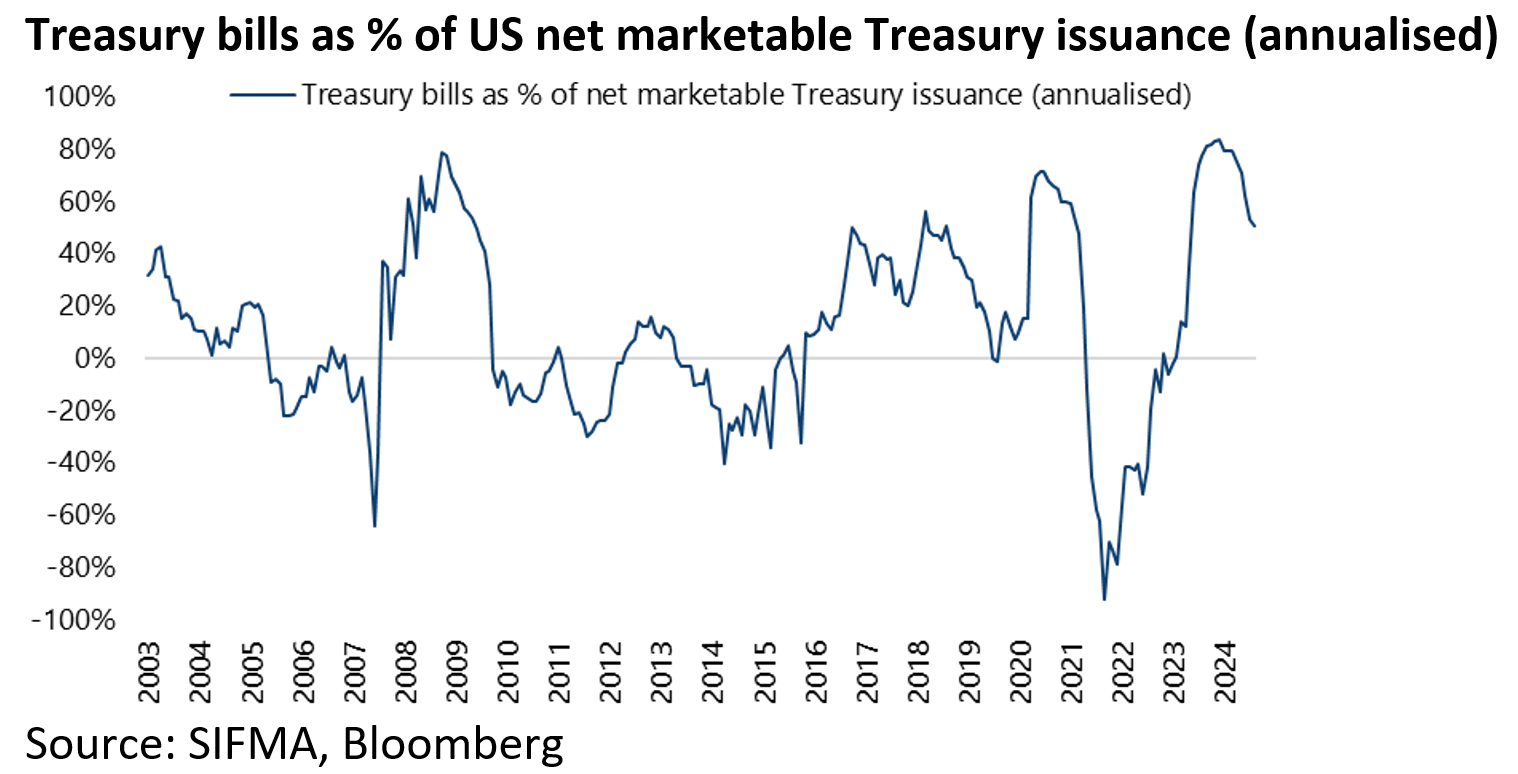

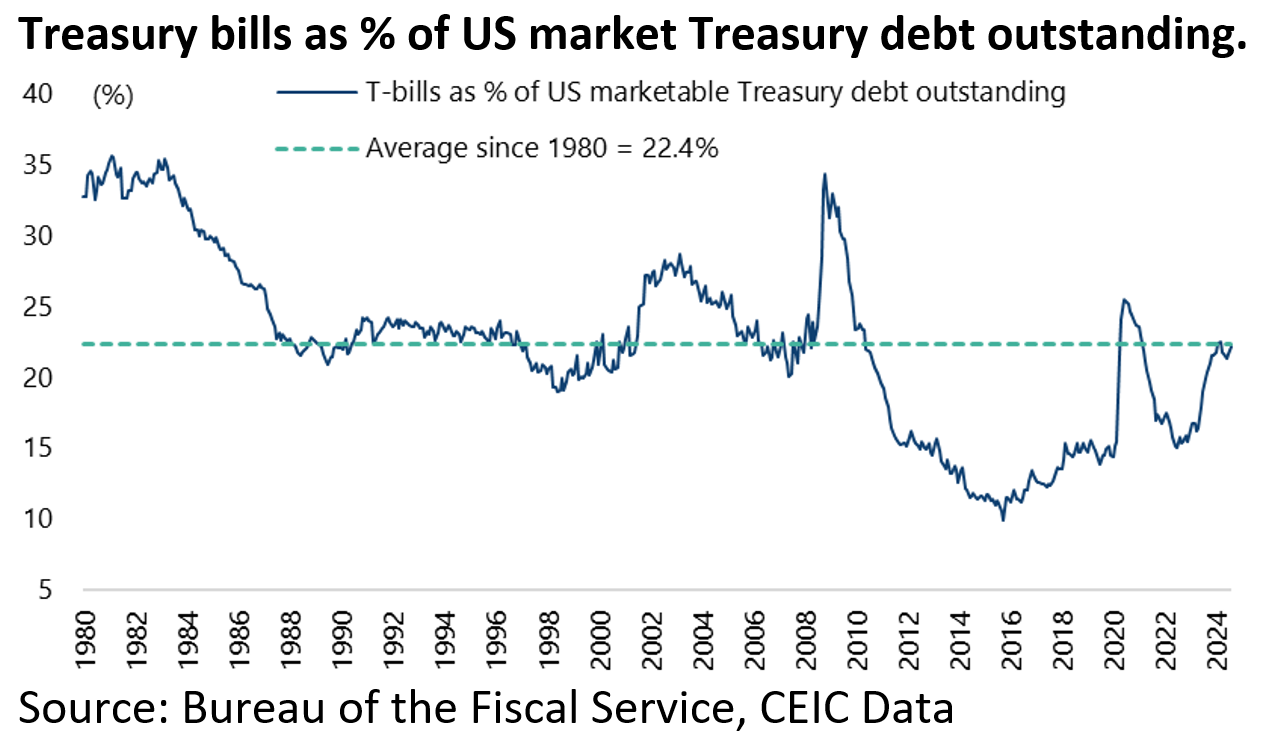

Treasury bills’ share of annualised net marketable Treasury debt issuance on a flow basis rose to a peak of 83.5% in December though it has since declined to 50.9% in August.

The authors argue that the resort to reliance on short-term funding marks a radical departure from the traditional pattern for the Treasury to engage in regular and predictable issuance.

They also go so far as to argue that this “activist Treasury issuance” amounts to a form of stealth QE since it has the same de facto impact as quantitative easing in terms of an easing of monetary policy.

Treasury Bills Funtioning More Like Currency Than Ever Before

If the above is interesting, the authors also make a valid point when they argue that what they call the “money-likeness” of Treasury bills has grown in the quanto easing era.

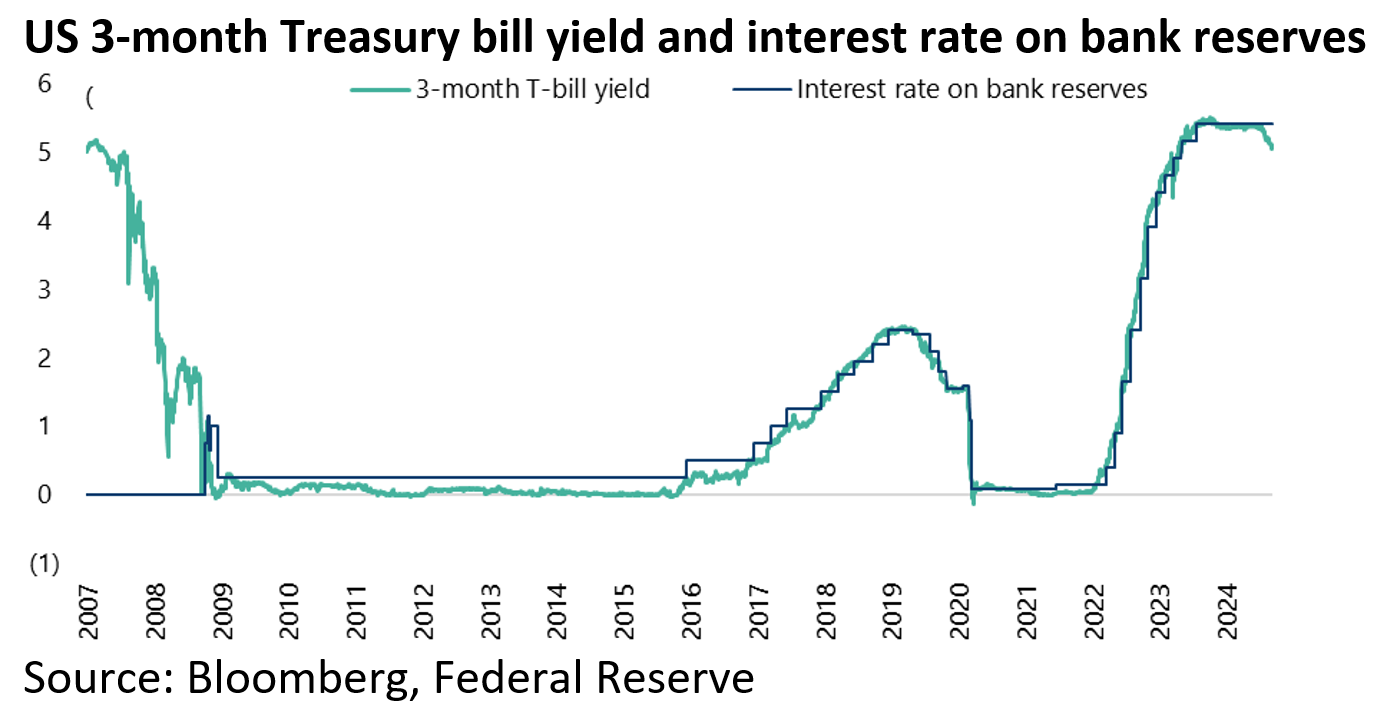

This is because prior to 2008 so-called base money constituted the zero-yielding liabilities of the central bank, namely currency and bank reserves.

But with the adoption of quantitative easing, the Fed began paying banks interest on reserves in October 2008, and as a result the yield on bank reserves and Treasury bills became very similar.

Thus, the interest rate on bank reserves is now 5.4%, compared with the 3-month Treasury bill yield of 5.06%.

The authors write: “The economic substitutability between bills and reserves became greatly enhanced. Bills are not part of base money, but they are quasi-money”.

The above is an interesting point conceptually and provides another example of the ever-greater blurring of the distinction between fiscal and monetary policy which is the consequence of 16 years and counting of unorthodox monetary policy – just as the big increase in central banks’ ownership of their own government bond market is a consequence.

Draining of the RRP Blunted the Impact of Fed Tightening

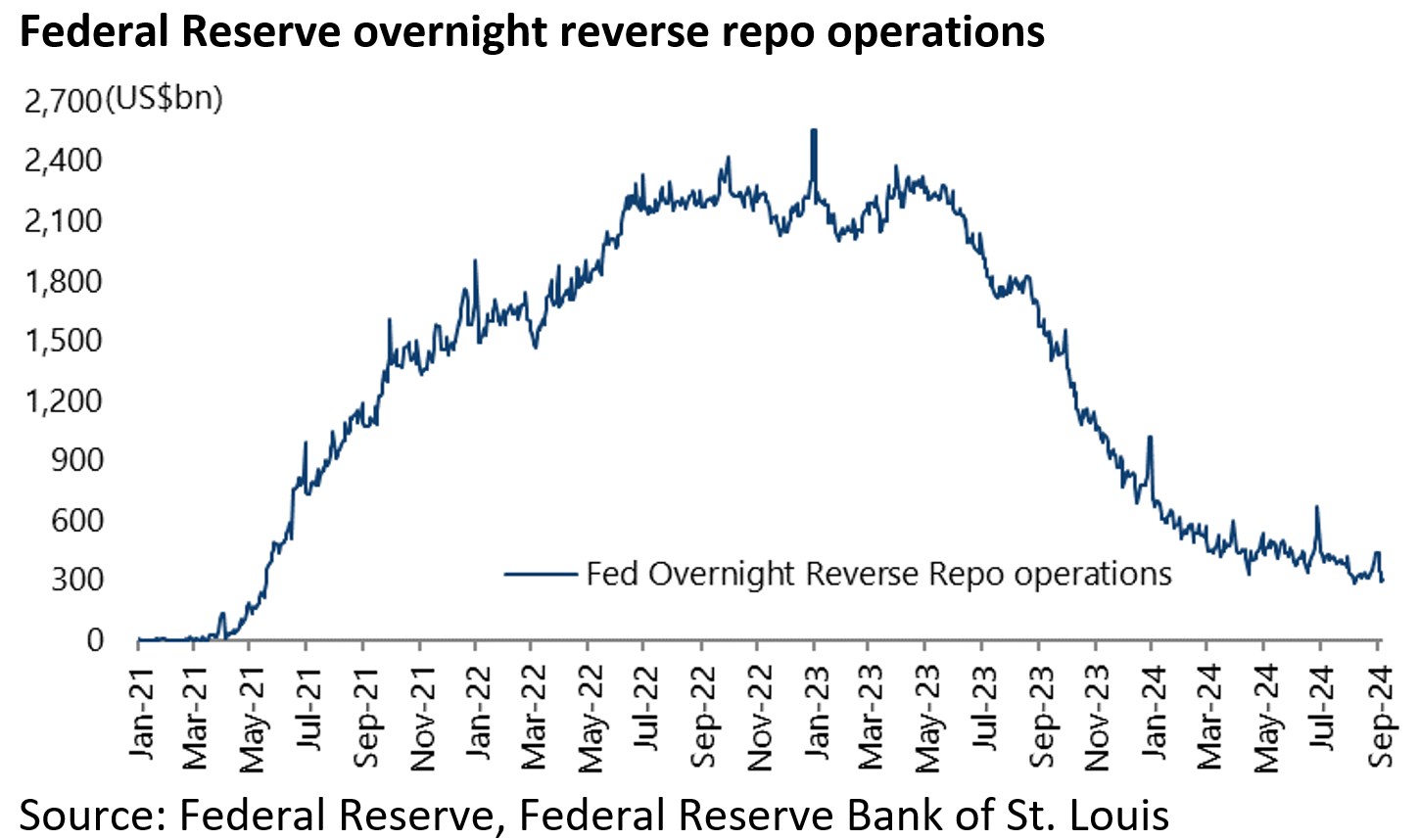

But from a practical market standpoint the greatest market impact of so-called “activist Treasury issuance” was probably the draining of the reverse repo (RRP) balance from a peak of US$2.55tn in late 2022 to US$299bn now with most of the decline taking place last year.

If the Treasury bill issuance impacted the RRP it did not impact bank reserves and so, the authors argue, did not impact monetary policy.

The impact would have been very different if the reduction in money balances had been in favour of assets with long-term duration risk like Treasury bonds.

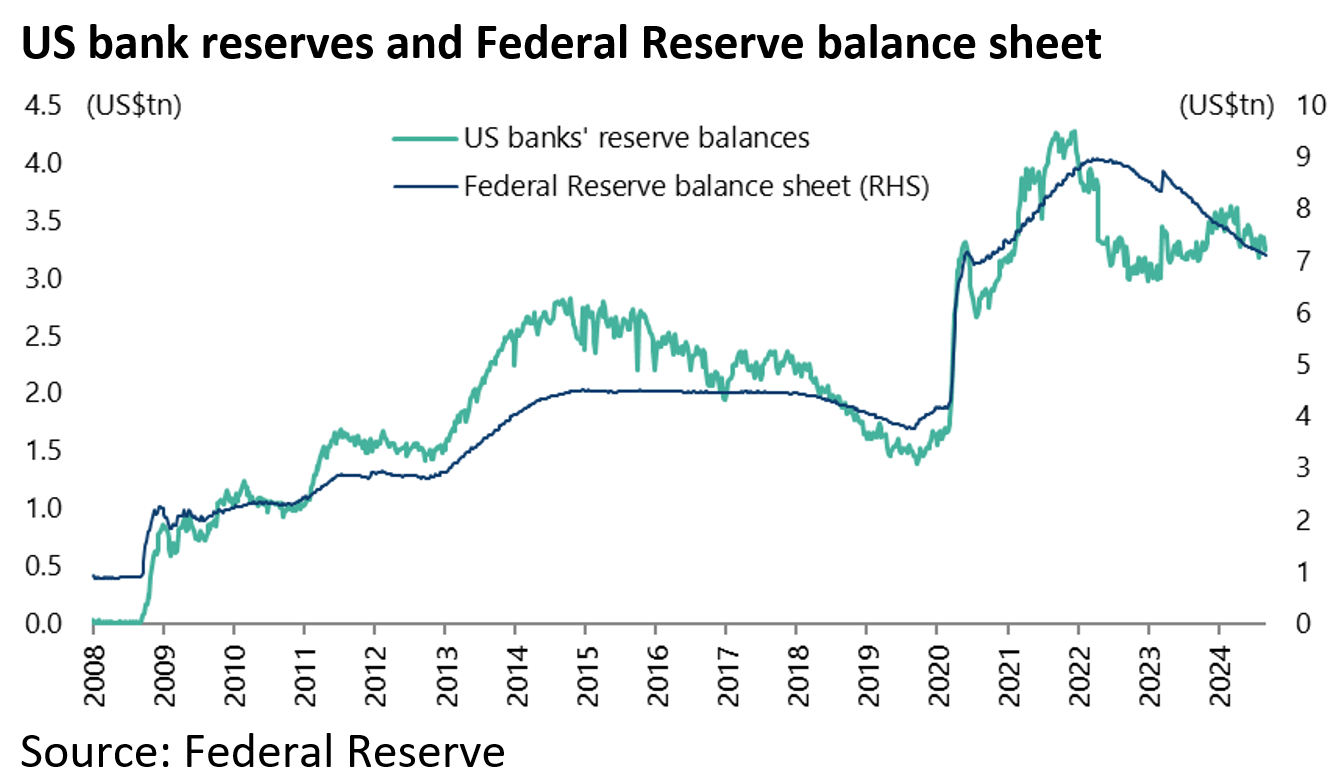

The authors further argue that the Treasury’s de facto “sterilization” of the recent period of quantitative tightening is illustrated by the fact that bank reserves have largely treaded sideways since the Fed began to contract its balance sheet in June 2022.

Thus, the Fed balance sheet has declined from US$8.9tn at the beginning of June 2022 to US$7.1tn, while bank reserves have fallen only from US$3.36tn to US$3.26tn over the same period.

Remember the Fed recently reduced its pace of quanto tightening from up to US$95bn/month to US$60bn/month starting in June in what also amounts to a clear easing of monetary policy.

This seems to have been prompted by the desire to stop bank reserves declining to anywhere near the level in late 2018, which prompted a severe liquidity squeeze and a Powell pivot as convulsions in the repo market caused an abrupt end to the previous episode of quanto tightening.

Growing Problems with Short Term Bills

Moving away from the arcane details of monetary policy, the report also highlights some obvious problems with the growing short-term bill issuance which laymen can easily understand.

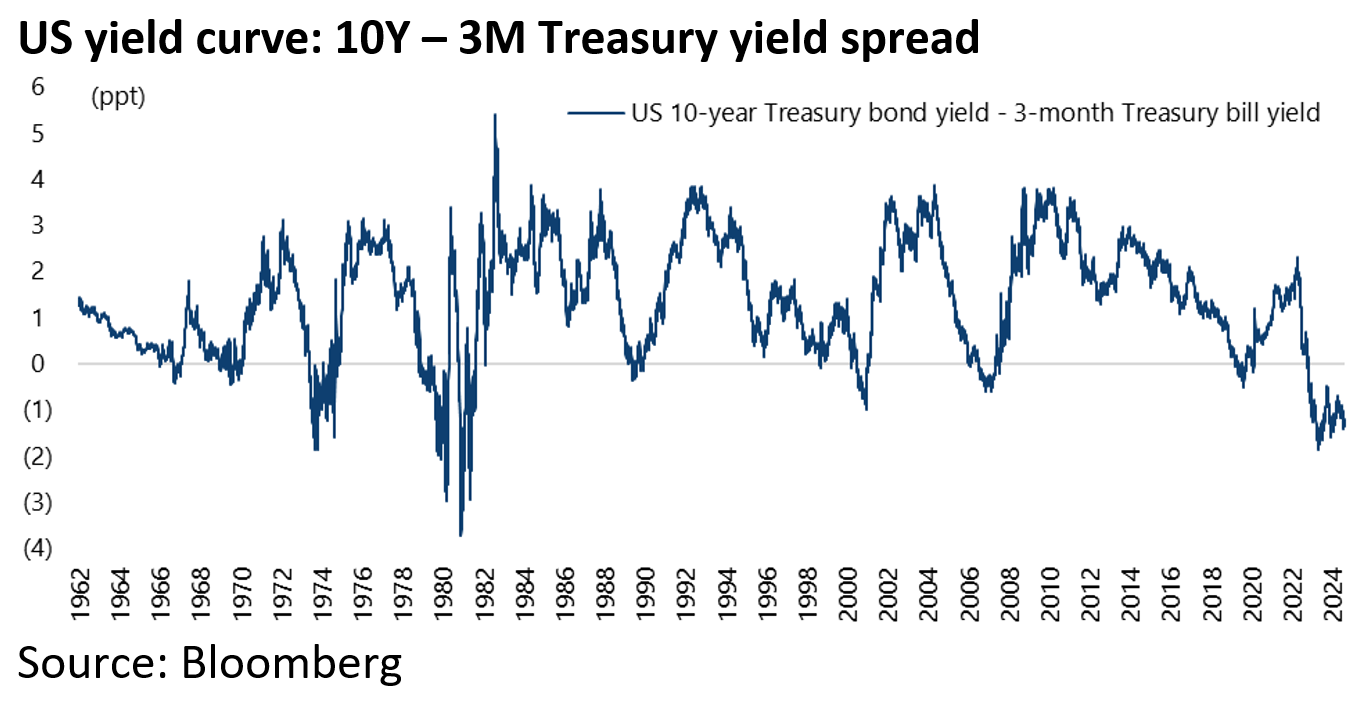

First, the Treasury is funding at the most costly point on the yield curve given its still inverted nature.

Second, it is also subject to growing rollover risk.

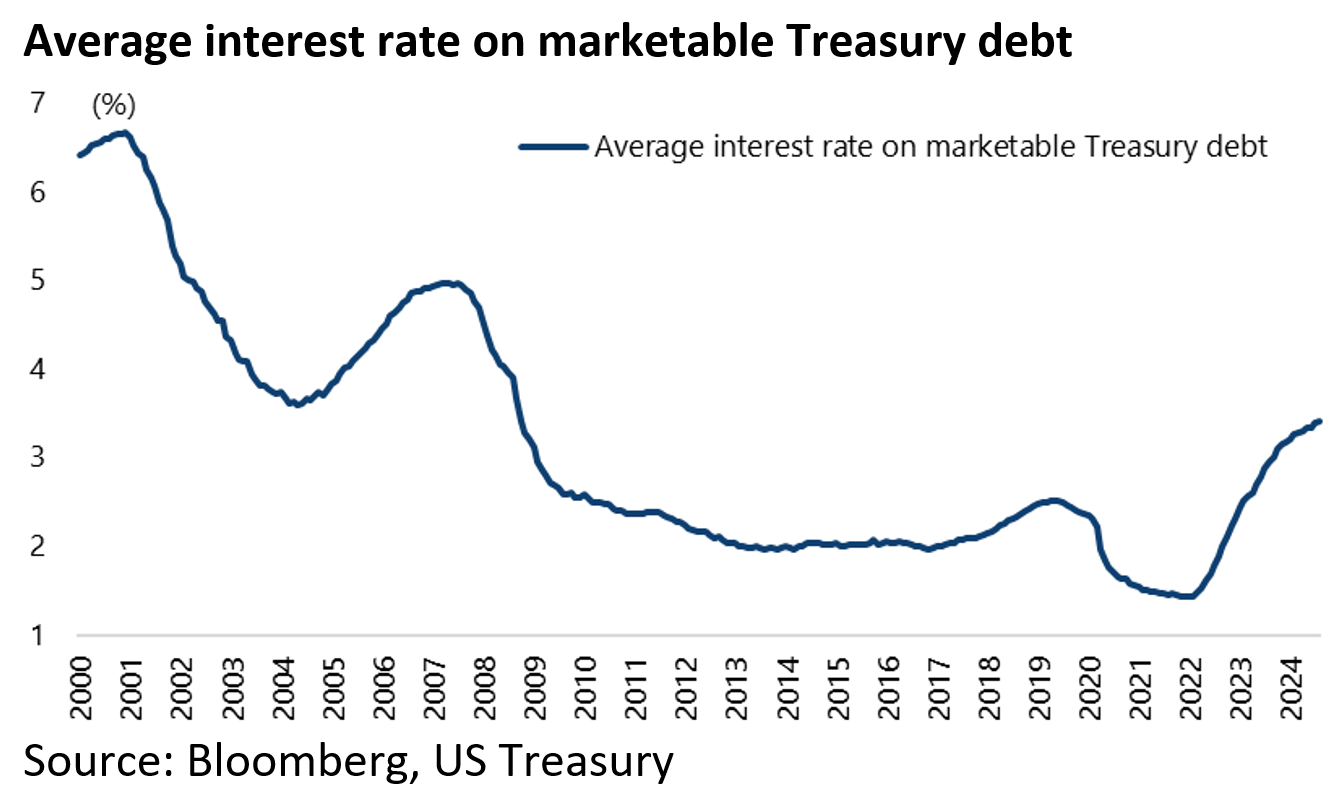

On this point, the authors note that the average interest rate paid on marketable Treasury debt is at its highest since 2008, while debt servicing has nearly become the single-largest outlay for the government.

The average interest rate on marketable Treasury debt has risen from a low of 1.42% in January 2022 to 3.42% in August, the highest level since September 2008.

The obvious question is when do markets start to worry about all this, with one obvious trigger the Treasury quarterly refunding announcement in terms of a sudden increase in the sale of long-term Treasury bond triggering a rise in what bond geeks call the term premium.

With a presidential election pending, it is no surprise that no such dramatic move was made in the latest quarterly refunding announcement at the end of July.

Meanwhile, the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, a panel of investors, dealers and other market participants, recommended in a report released on 31 July a Treasury bill share averaging around 20% of total Treasury debt outstanding over time.

The committee previously recommended a 15% to 20% range. On a stock basis, Treasury bills’ share of US marketable Treasury debt outstanding has risen from 15.1% in July 2022 to 22.5% in March and was 22.2% in August.

But clearly short-term issuance has been much larger of late on a flow basis as already noted.

A Violent Treasury Bond Response Could be Looming in Early 2025

Meanwhile, as Miran and Roubini note, a potential catalyst is looming in terms of the expiry on 2 January 2025 of the bipartisan agreement to suspend the debt limit embodied in the 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act.

The inauguration of the next president will take place 18 days later on 20 January 2025.

It is hard to question Miran’s and Roubini’s conclusion that “the longer Treasury waits to term out the bills, the more violent the response will be when Treasury finally undertakes it, since the stockpile of bills grows larger every day”.

That is, unless, of course the authorities, be they fiscal or monetary joined at the hip as they increasingly are, simply decide to fix long-term yields in some form of yield curve control.

The views expressed in Chris Wood’s column on Grizzle reflect Chris Wood’s personal opinion only, and they have not been reviewed or endorsed by Jefferies. The information in the column has not been reviewed or verified by Jefferies. None of Jefferies, its affiliates or employees, directors or officers shall have any liability whatsoever in connection with the content published on this website.

The opinions provided in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice. Readers should assume that the author and/or employees of Grizzle hold positions in the company or companies mentioned in the article. For more information, please see our Content Disclaimer.