Japan has been one of the stock markets favoured by this writer. There has recently been some political noise with the departure of yet another Japanese prime minister.

Shigeru Ishiba resigned on 7 September when it became clear that he was going to be forced out by a party vote.

Such an outcome always seemed inevitable following the loss of a LDP majority in the Upper House election held in July. The LDP also does not have a majority in the Lower House of the Diet.

The LDP party members selected Sanae Takaichi as the new LDP president on 4 October, who was subsequently confirmed by the Diet as the first ever lady Prime Minister on 21 October.

The election of Takaichi as Japan’s Prime Minister is a positive for the stock market as it suggests a more dynamic leadership in the Shino Abe mode.

Takaichi is a protégé of the late prime minister and an advocate of more doveish monetary policy.

It is also interesting that Takaichi has formed a coalition with the conservative Osaka-based Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) ending 26 years of LDP coalition governments with the Komeito.

This will lead to more robust policies as regards both defence and immigration as the political process responds to the growth in right-wing populism in Japan.

There is growing evidence of a demographic divide in Japanese politics.

Data shows that more than 55% of the LDP votes in the Upper House election came from people aged over 70.

This suggests that the long ruling LDP’s core support will be literally dying out in coming years.

Implications of Japan’s Demographic Cliff

Meanwhile one core issue which is upsetting Japan’s younger generation is that scant effort was made to reform Japan’s social security and medical system ahead of the country’s long anticipated demographic cliff.

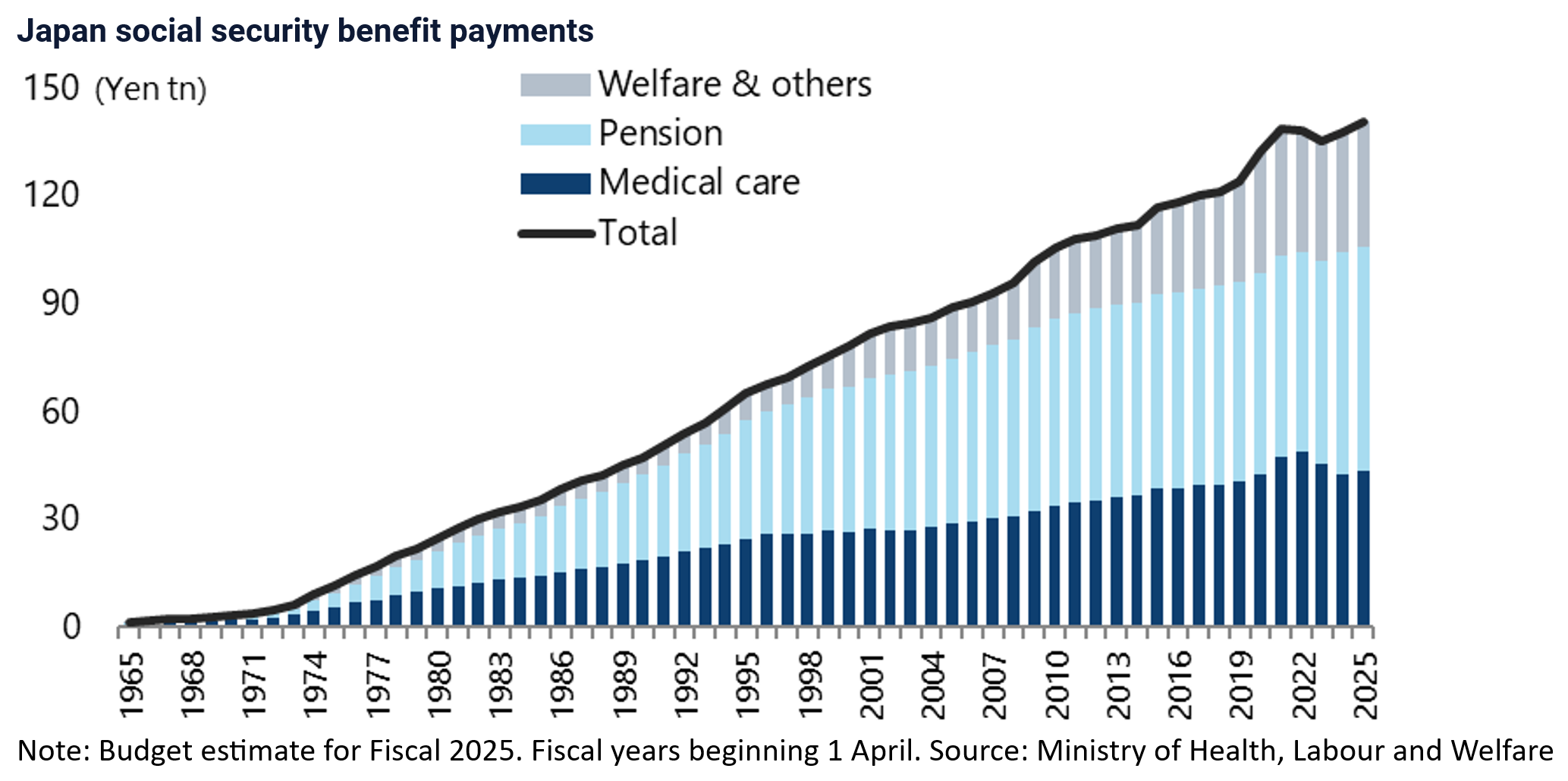

Thus, Japan is currently spending Y140tn or 22.4% of GDP a year on social security and healthcare, while working Japanese are paying 15% of their gross wages on contributions to social security, and their employers another 15%.

Meanwhile the retired elderly aged over 75 only have to pay 10% towards their healthcare costs and 20% for those aged 70-74. Given that 36% of the population is now aged over 60 this is, understandably, causing rising tensions between the generations.

The other issue starting to cause tensions is a growing pushback against immigration. Thus, Justice Minister Keisuke Suzuki made headlines when he stated in late July at the Japan National Press Club in Tokyo that the proportion of foreigners in Japan could exceed 10% by 2040 (see Japan Times article: “Japan’s foreign population could top 10% in 2040, says justice minister”, 31 July 2025).

This raised eyebrows as did a NHK report in August that four Japanese municipalities were designated as “Africa’s hometowns” (see NHK report: “JICA’s plan to pair four Japanese ‘hometowns’ with African nations takes on a life of its own”, 28 August 2025).

If the actual level of immigration is only 2.8% of the population, it is easier to immigrate to Japan than many might assume given the country’s famed xenophobia.

For example, it has been possible to acquire a five-year entrepreneur visa for just Y5m (US$32,000).

The recipient of such a visa can then bring in relatives, including spouse and children but seemingly not parents, all of whom can then take advantage of the Japanese healthcare system.

In the case of those aged over 70 they only pay 10-20% of the medical cost, the same as Japanese nationals.

Such an offer has proved attractive, for example to middle-class Chinese.

Immigration data shows that 41,615 foreigners held such visas at the end of 2024, up 11% YoY, with Chinese nationals making up 2,741 or 52% of the total.

Meanwhile, in terms of the required capital investment for such a visa, the authorities hiked it to Y30m (US$192,000) in October.

Such companies are also now required to employ at least one full-time employee who is a Japanese citizen or permanent resident.

While it could be argued that immigration is a practical necessity for Japan, it is no surprise that populist pressures on the right of a kind long observed in America and Japan are now building.

The clearest manifestation of this so far is the populist and social media savvy Sanseito Party, which won a surprisingly large 14 seats in the Upper House election.

Its support base is mainly in the 30-40 year old age group and its main 2 policies are anti-immigration and increased handouts to address rising living costs.

Falling Wages and Rising Housing Prices Pressuring Japanese Youth

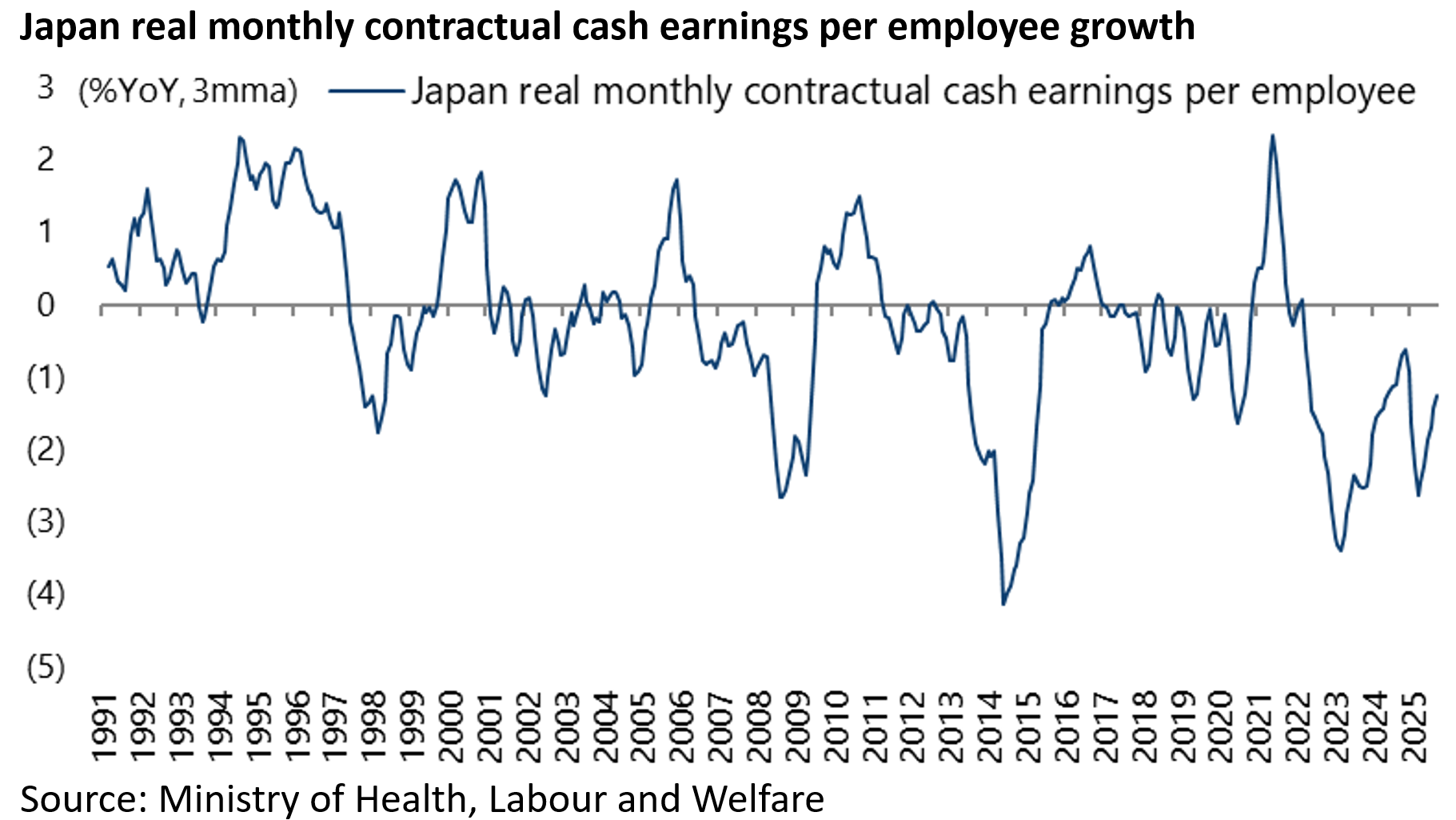

In Japan it remains the case that inflation is primarily driven by the cheap yen and this has continued to depress real wages. Real monthly contractual cash earnings per employee declined by an average 1.3% YoY in the three months to September.

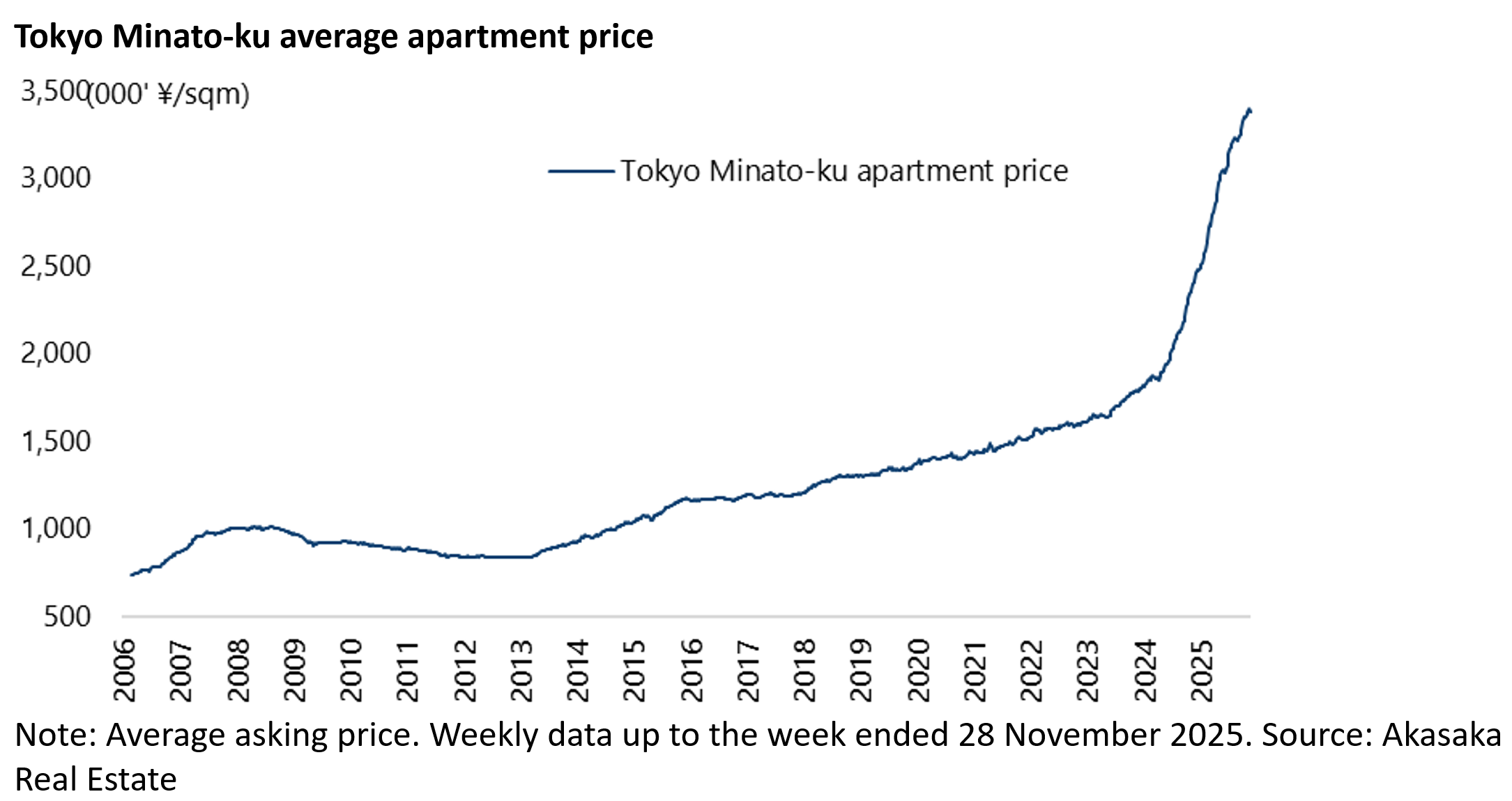

A further pressure point, at least in central Tokyo, has been rising property prices which has made property ever more unaffordable for those not on the housing ladder.

That is the consequence of years of ultra easy monetary policy and a central bank which remains deliberately behind the curve in terms of monetary tightening.

Thus, high-end condos in central Tokyo have been transacting at increasingly higher prices.

The average asking price of apartments in Minato-ku, the district known for its high-end condos, has risen by 40% over the past 12 months to Y3.4m/sqm, according to Akasaka Real Estate.

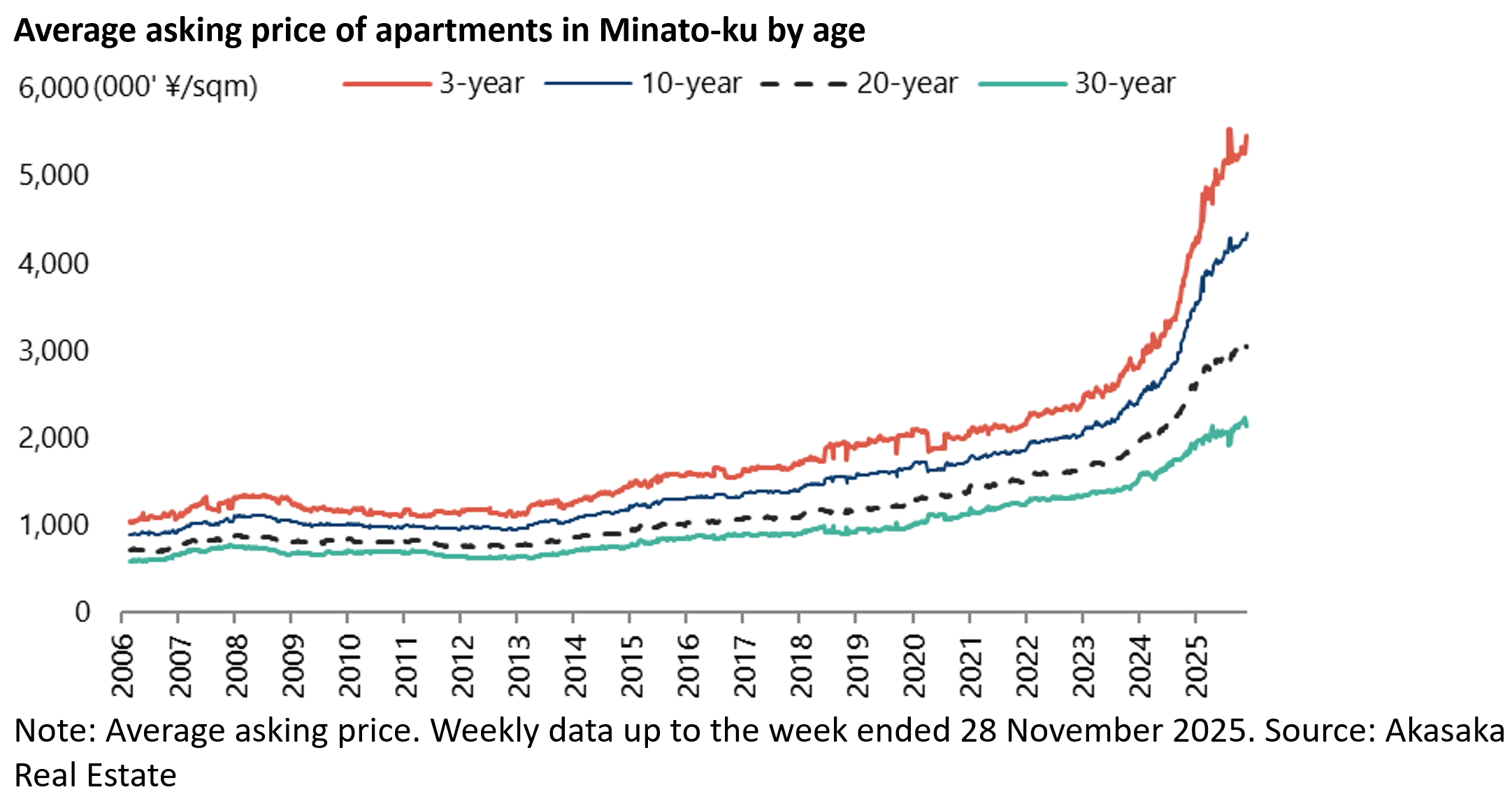

The divergence in price between new property and second-hand property in the same location has also become enormous.

Thus, the average price of apartments aged three years or less in Minato-ku is now Y5.5m/sqm, or 2.6x the average price of Y2.1m/sqm for apartments aged 30 years and over.

The State of US-Japan Tariffs

Still if all of the above is a breeding ground for populism, there is so far a remarkable lack of any evidence of any populist backlash against the bullying tactics of the Trump administration as regards the tariff negotiations with Japan.

One problem has been that the negotiations have encountered an ongoing gulf between what the Japanese side believed they had agreed and what President Trump stated had been agreed.

Still the US president finally signed an executive order on 4 September making a baseline 15% tariff rate official, effective 16 September, which means automakers will not have to pay the previously threatened 27.5%.

But the price paid for the US agreeing to the lower tariff is a commitment by Japan to invest US$550bn into the US.

On this point, there remains a lot of room for continuing disagreement.

The Japanese view seems to be that the US$550bn includes loan guarantees from Japanese public financial institutions whereas this is most unlikely to be the interpretation in Washington.

Indeed Trade Secretary Howard Lutnick said on US TV in early September that, in return for lower tariffs, the Japanese “have given President Trump US$550bn for President Trump to direct where and how he wants it invested in America”.

Then there is also the issue, still seemingly to be agreed, of how the profits on any such investments, assuming there are any, are to be divided.

The Donald’s original request was for a 90/10 split! Apparently, the memorandum of understanding signed on 4 September by Lutnick and the main Japanese negotiator, Minister in Charge of Economic Revitalization Ryosei Akazawa, stated that Japan and America will evenly split the cash flow generated until Japan’s investment is paid off, at which point the US will take 90% of the proceeds and Japan 10% (see Financial Times article: “Trump to direct Japan’s trade deal cash”, 9 September 2025).

All of the above would seem natural fodder for populist politicians to exploit.

But there is no sign as yet of any such pushback politically, despite private comments about extortion tactics, doubtless in large part because of Japan’s reliance on the US for the country’s defence.

Indeed the obvious risk is that if Japan does not agree to Trump’s tariff agenda, the US president will demand that Japan pays more for its defence.

About 53,000 US troops are still stationed in the country.

On this point, it is the case that this writer has always viewed the relationship between the US and Japan post-1945 as that of older brother and younger brother.

And older brothers tend to like to bully younger brothers.

Japanese Stocks are on the Move

As for the Japanese stock market, it has continued to make solid gains, up 21.3% year to date, despite the tariff concerns helped by continuing evidence of improving corporate governance.

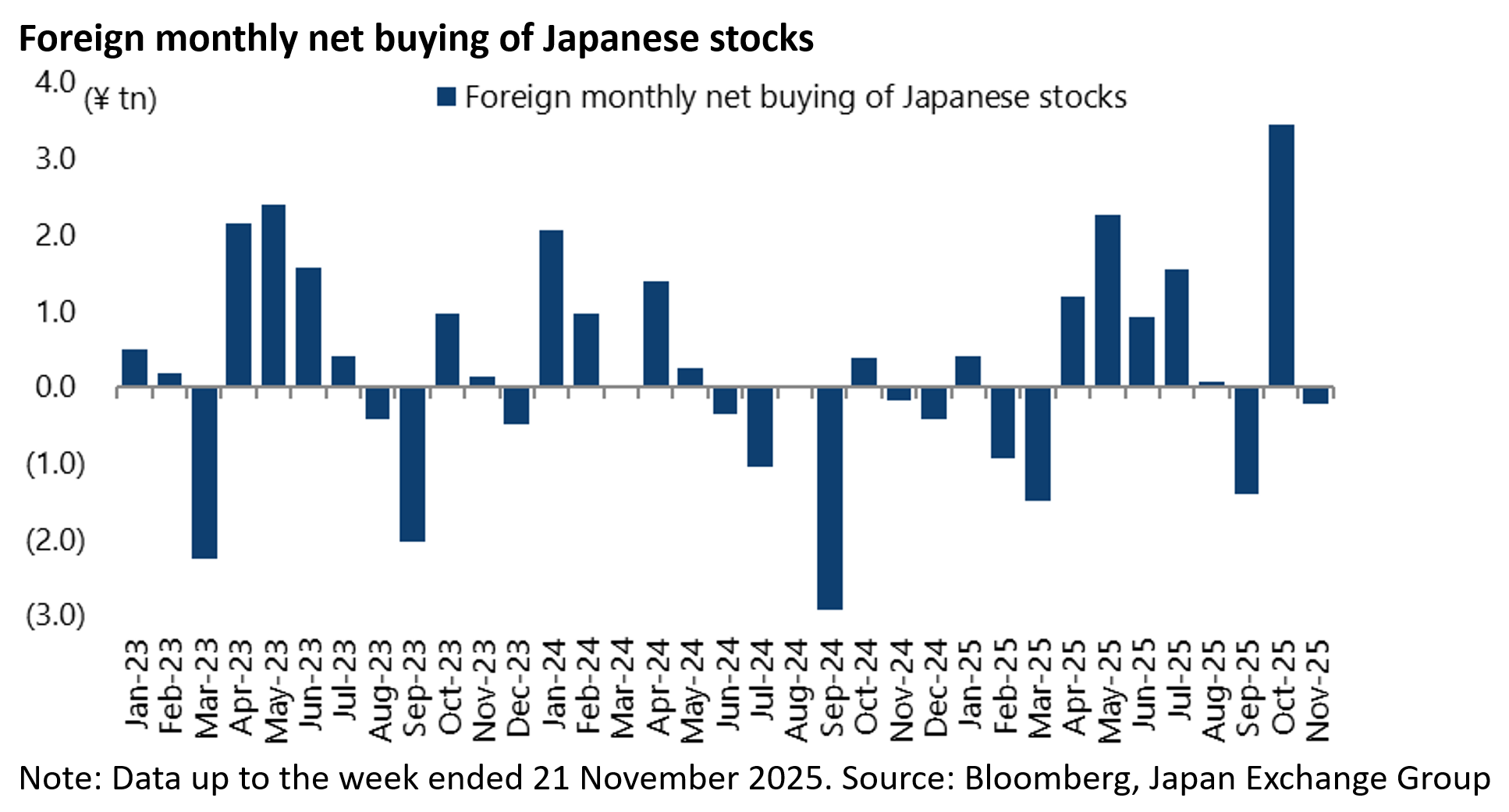

Topix-listed firms have announced Y11.5tn of share buybacks since the start of the fiscal year while foreign investors have been net buyers for six of the past eight months, purchasing a net Y7.82tn worth of Japanese stocks since April, after selling a net Y2.01tn in 1Q25.

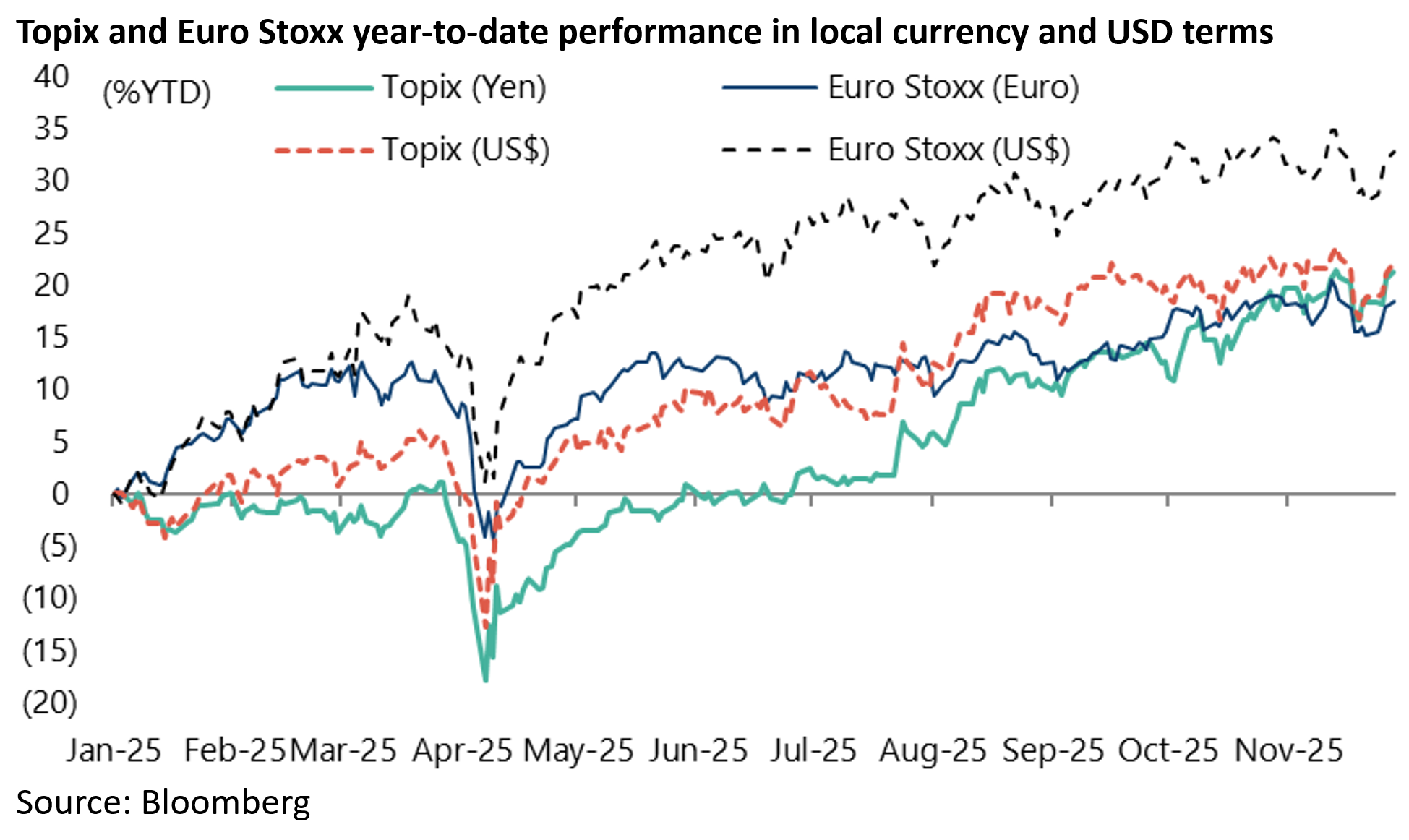

Indeed the Topix is up about the same as the Eurozone’s Euro Stoxx Index year-to-date in local currency terms with the difference in US dollar terms explained by the euro’s much greater appreciation against the US dollar.

Thus, the Topix has risen by 21.3% year-to-date in yen terms and is up 22% in US dollar terms. By contrast, the Euro Stoxx Index is up 18.4% in euro terms and 32.7% in US dollar terms over the same period.

Japan is Showing Good Growth, but what about Interest Rates?

BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda remains as cautious as ever, as regards monetary tightening.

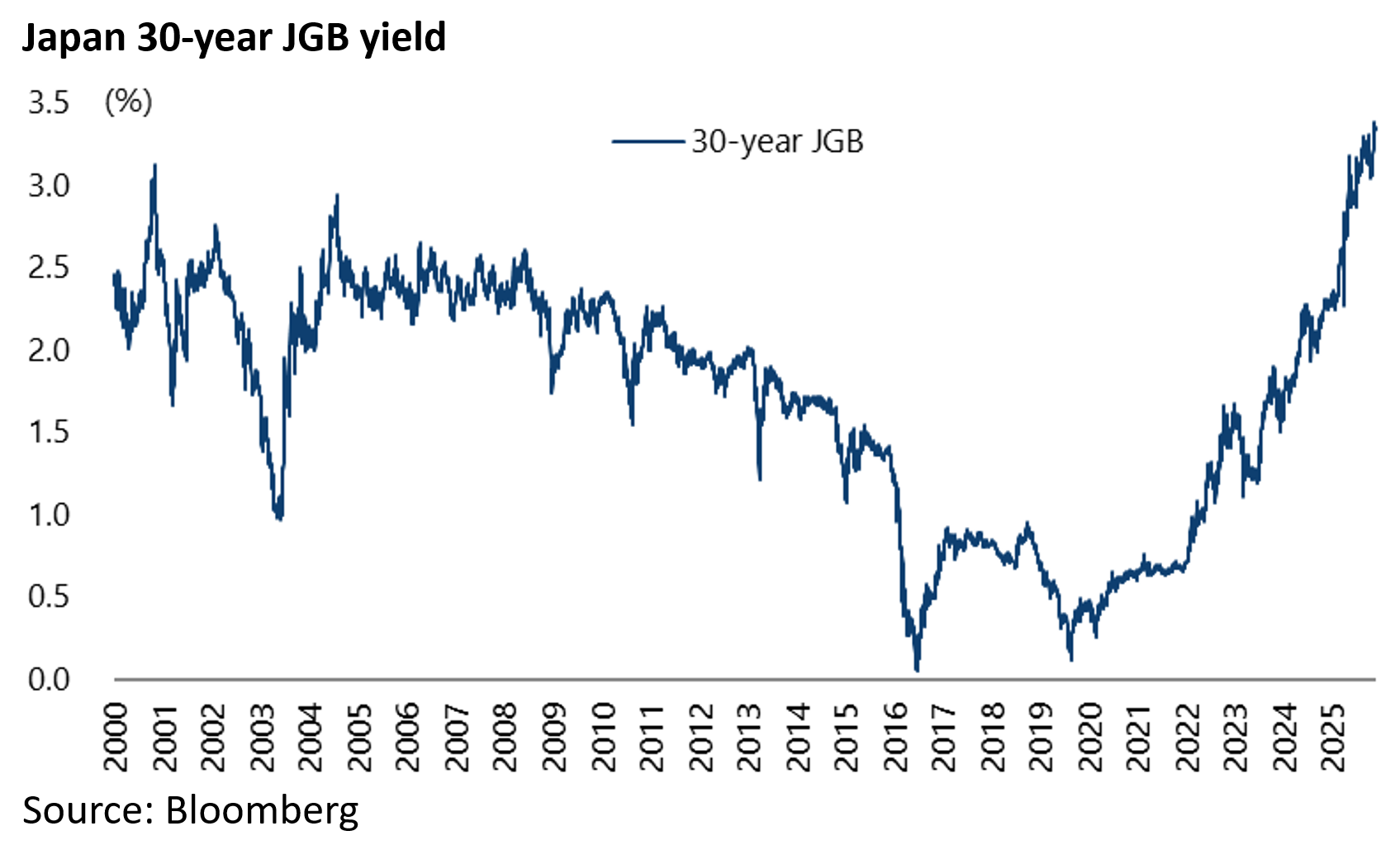

The risk about being too cautious is a further steepening of the yield curve with the 30-year JGB yield now 3.35%.

For such reasons there is the potential for another 25bp rate hike at the 19 December BoJ policy meeting to 0.75%.

Such an outlook clearly creates the potential for yen appreciation; though the risk is Ueda’s innate caution in the sense that he may well want to wait for evidence of whether the tariffs impact growth negatively both in Japan and, perhaps more importantly, in the US.

For such reasons, money markets are only forecasting 15bp of BoJ tightening by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, that the Japan stock market is trading at a new record high reflects in part the Tokyo Stock Exchange-driven corporate governance reform agenda.

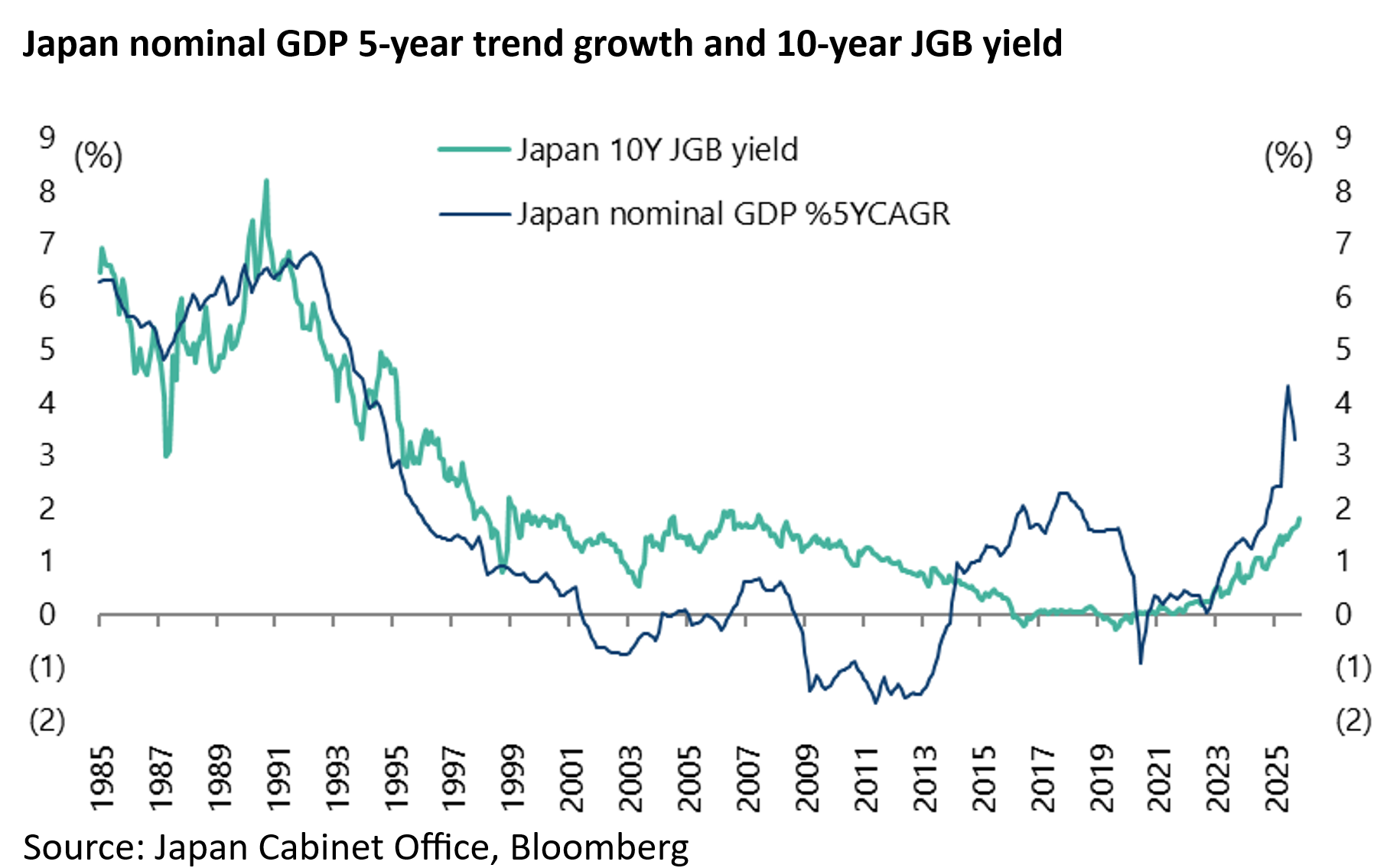

It also reflects the accumulating evidence that Japan has returned to solid nominal GDP growth which is good for equities and bad for government bonds.

Japan nominal GDP rose by 3.9% YoY in 3Q25 and is up an annualised 3.3% over the past five years, up from an annualised 0.0% in the five years to 3Q22.

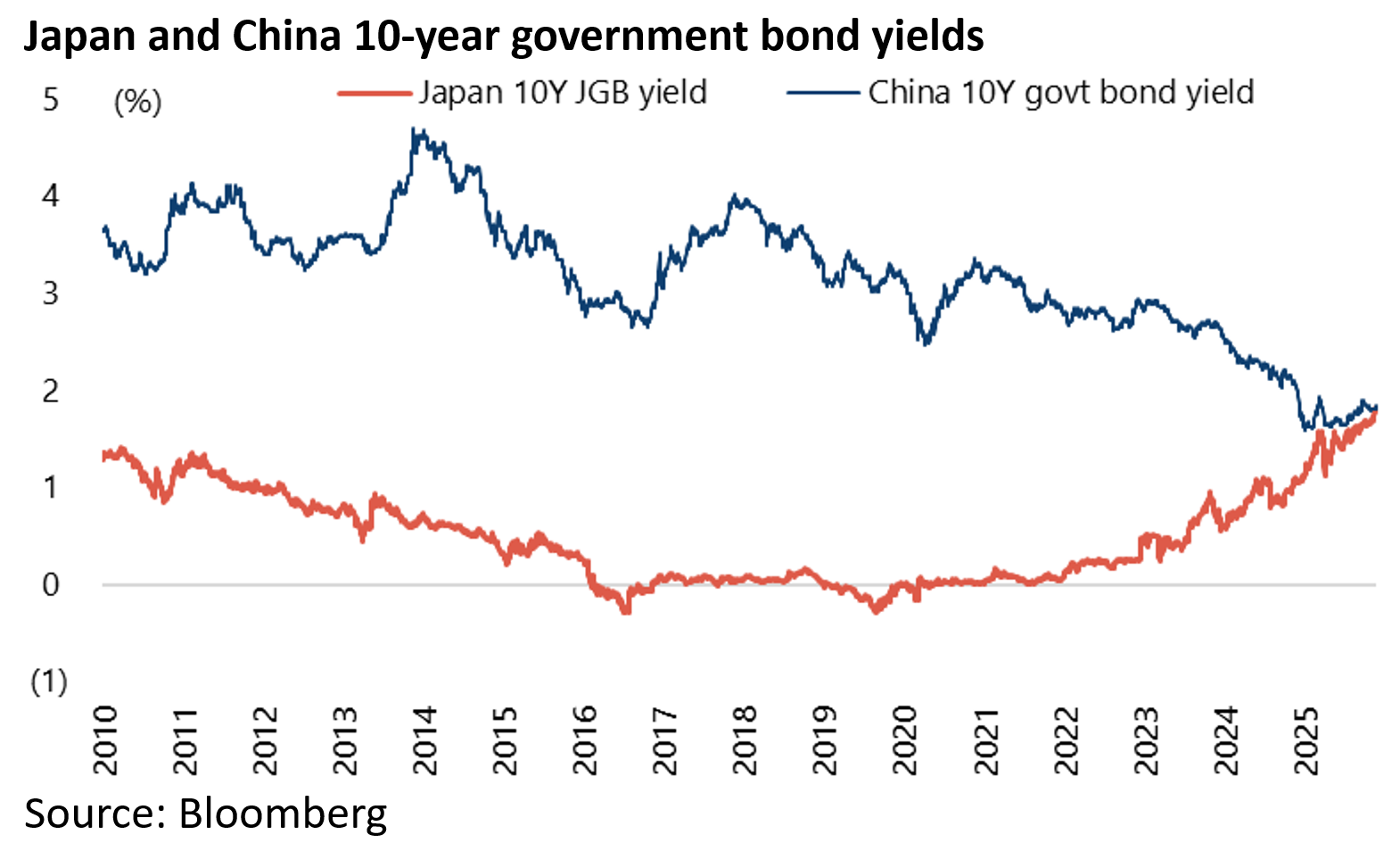

While the 10-year JGB yield has risen from a negative 0.29% in August 2019 to 1.81%.

This is also why both nominal GDP growth and ten-year government bond yield look on the point of crossing their Chinese counterparts.

China nominal GDP slowed to 3.7% YoY in 3Q25, compared with 3.9% YoY in Japan.

While the China 10-year government bond yield has declined from a peak of 4.7% in November 2013 to 1.83% or “only” 2bp above the 10-year JGB yield, down from 407bp in November 2013.

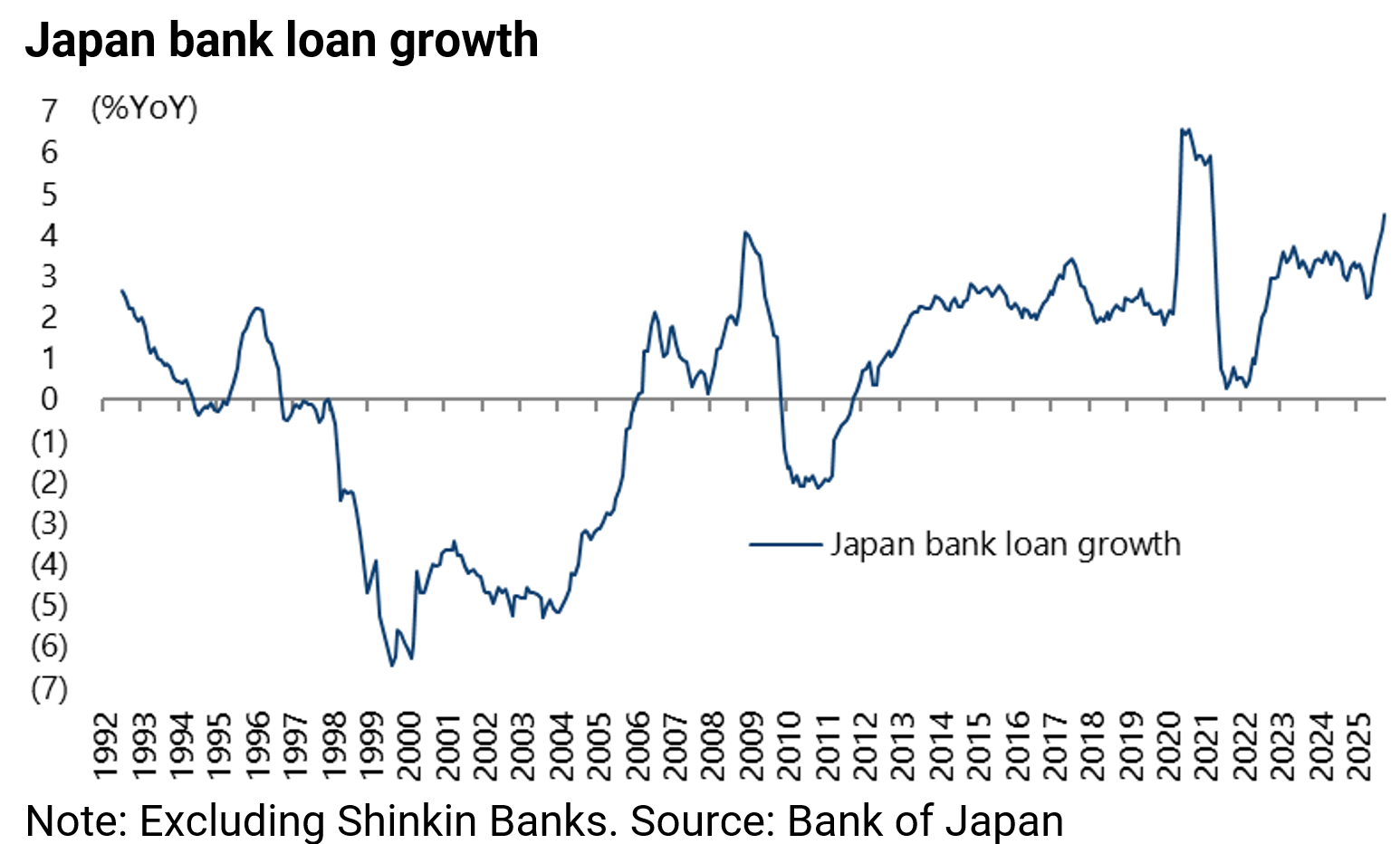

Meanwhile, bank loan growth remains healthy running at 4.5% YoY in October.

This is the strongest loan growth in Japan, excluding the post-pandemic period, since the data series began in 1992 following the peak of the Bubble Economy in 1990.

The views expressed in Chris Wood’s column on Grizzle reflect Chris Wood’s personal opinion only, and they have not been reviewed or endorsed by Jefferies. The information in the column has not been reviewed or verified by Jefferies. None of Jefferies, its affiliates or employees, directors or officers shall have any liability whatsoever in connection with the content published on this website.

The opinions provided in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice. Readers should assume that the author and/or employees of Grizzle hold positions in the company or companies mentioned in the article. For more information, please see our Content Disclaimer.