With money markets now discounting three Fed rate hikes this year, and maybe even four, and the 10-year Treasury bond yield approaching 3% again, the attitude of the Fed has become critical.

In this respect, there is perhaps less clarity than usual because the new Fed chairman Jerome Powell is a lawyer by training who appears to have no strong ideological views on monetary policy in stark contrast to his predecessors, Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, both of whom as academic economists had a strong theoretical belief in the efficacy of unorthodox monetary policy or ‘quanto easing‘.

Will Powell Follow Yellen’s Dovish Script?

In the absence of such clarity, markets had tended to assume that Powell will follow the script of the dovish Yellen. This may prove to be the case. But it should be noted that even Yellen diverged from her narrow “targeting core CPI/PCE” approach last year when she continued to raise rates, even though core CPI and core PCE inflation were weaker than the Fed expected and running well below the official 2% target.

Yellen rationalized this at the time by saying that the decline in inflation was “transitory”. This has so far proved to be the case, with reported inflation rising this year. Meanwhile, the other point is that Powell may just not be as dovish as the markets had assumed him to be. On this point, a reading of a statement attributed to Powell in the minutes of the October 2012 FOMC meeting are revealing.

Discussing his concerns about the growing size of the Fed balance sheet (then US$2.8 trillion and expected to reach US$4 trillion by 1Q14) and related concerns about encouraging ‘risk taking’, Powell stated:

These are extremely interesting comments. First, they suggest that Powell is not the instinctive dove markets at least initially believed, or perhaps President Trump still believes.

Second, it highlights that Powell understood back in 2012 the technical fact, usually ignored by theoretical academic monetary economists, that the Fed’s policies had encouraged a massive ‘short volatility’ trade. This is, of course, what became painfully obvious when the VIX soared in February on the stock-market correction and those speculators ‘short vol’ lost a lot of money quickly.

Remember that the VIX surged from a low of 9.15 in early January to a closing high of 37.3 and an intra-day high of 50.3 in early February (see following chart). The previous decline in the VIX to unprecedentedly low levels, while driven by Fed policy, has also been further accentuated by the growth in machine-driven trend-following automated trading strategies using ETFs and other passive related investments, as previously discussed in this column.

CBOE S&P500 Volatility Index (VIX)

Source: Bloomberg

A Desire to Curb Risk Taking

With this scare having now happened, it will be interesting to see if the VIX returns to its previous low levels. This is extremely unlikely if the Fed continues on its tightening course. The VIX ended the past quarter at 19.97 and is now 16.88.

Meanwhile, it’s important to understand that the man now running the Fed understands that markets can be more dynamic than many academic economists appreciate. This means both that he will want to normalize monetary policy, but also that he will be hyper aware of the collateral damage that can result from the attempt to normalize.

Still, the clear risk for markets is that Powell will prove more hawkish than assumed out of a desire to curb the ‘risk taking’ triggered by a long period of easy money. On this point it is also interesting to note that Powell stated in a speech on January 7, 2017 at the American Finance Association in Chicago: “If risk taking does not threaten financial stability, it is not the Fed’s job to stop people from losing (or making) money.”

A Growing Deficit

Meanwhile the aggressive fiscal stimulus, which is the result of the Trump administration’s tax cuts, is a further reason to keep tightening monetary policy from a conventional economist’s standpoint since fiscal policy has been loosened dramatically in the US.

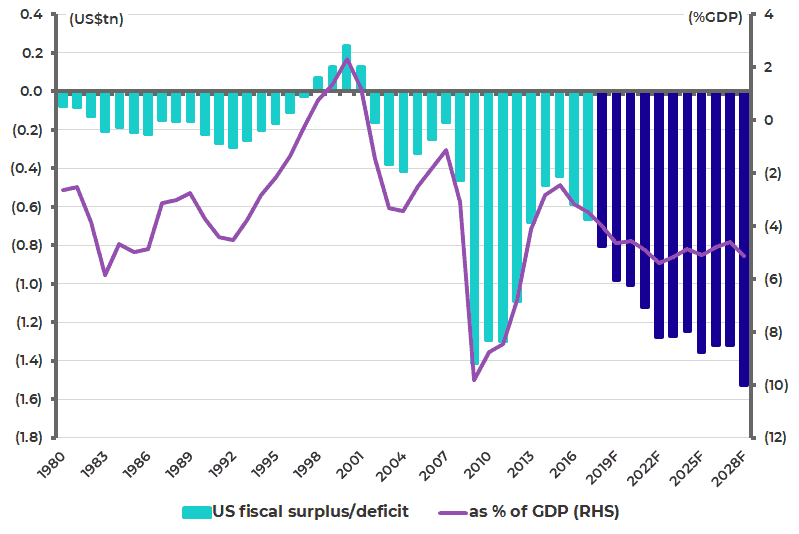

The fiscal deficit is projected by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to rise from US$665 billion or 3.5% of GDP in 2017 to US$981 billion or 4.6% of GDP in 2019 and will exceed US$1 trillion by 2020 (see following chart). It also needs to be remembered that total US government debt is now 105.4% of GDP and is projected by the Congressional Budget Office to rise to 113.6% of GDP by 2026.

US Fiscal Balance and Total Government Debt as % of GDP

Source: Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

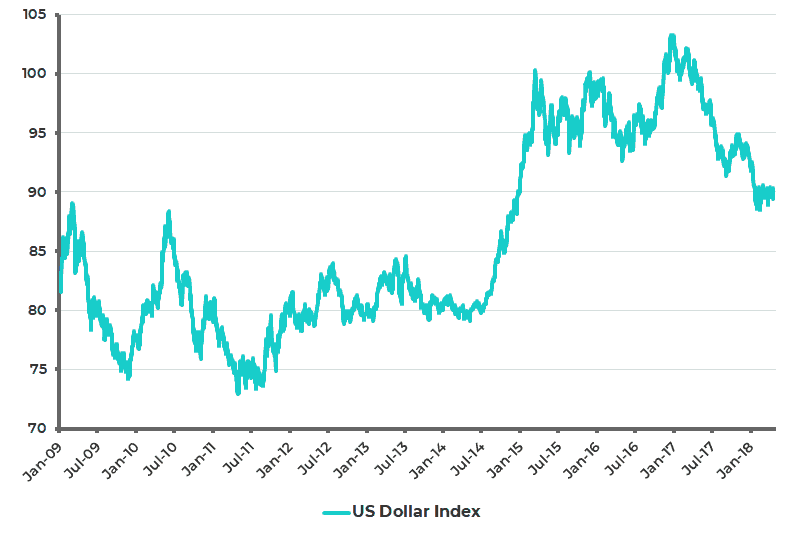

This rapid fiscal deterioration has become more relevant in market terms because this year has, so far, seen the combination of a sell-off in the bond market and a continuing weakening in the US dollar in the face of newsflow which should have seemingly been US dollar bullish, such as US tax reform leading to rising US GDP growth forecasts and rising Fed tightening expectations. Thus, the US Dollar Index has declined by 2.0% year-to-date, following a 9.9% decline in 2017 (see following chart).

US Dollar Index

Source: Bloomberg

That the dollar has continued to weaken suggests, among other things, that foreigners have become more nervous about funding the US deficit at a time when Treasury bond issuance is growing. The US Treasury expects to borrow US$955 billion this fiscal year, up from US$519 billion in 2017, and will borrow around US$1.1 trillion in each of the next two years.

Meanwhile, the core CPI inflation reading for March has seen a further pickup in reported inflation helped by the base effect since core CPI declined by 0.1%MoM in March 2017, the first month-on-month decline since January 2010, with the YoY inflation rate slowing from 2.2% in February 2017 to 2.0% in March 2017. US core CPI inflation accelerated from 1.8%YoY in February 2018 to 2.1%YoY in March 2018 (see following chart). But from now on the base effect becomes less supportive.

US Core CPI Inflation and Shelter Costs

Source: US Bureau of Labour Statistics

About Author

The views expressed in Chris Wood’s column on Grizzle reflect Chris Wood’s personal opinion only, and they have not been reviewed or endorsed by Jefferies. The information in the column has not been reviewed or verified by Jefferies. None of Jefferies, its affiliates or employees, directors or officers shall have any liability whatsoever in connection with the content published on this website.

The opinions provided in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice. Readers should assume that the author and/or employees of Grizzle hold positions in the company or companies mentioned in the article. For more information, please see our Content Disclaimer.